Ten years back when I had traveled to Kinnaur it was on a bus from Shimla. Sitting at a window seat my heart was in my mouth for most of the treacherous journey as the bus hurtled precariously on those winding mountain-hugging roads. Below, deep down in the gorge flowed the Sutlej. In 2003 I was with friends. This time round I was with family, driving! The decision was something I would regret. Starting from Delhi at 6 in the morning our first night-halt is at Kumarsain forest guesthouse (FGH), some eighty kilometers beyond Shimla.

It’s a small town overlooking a vast valley. We leave Kumarsain by ten in the morning. On the way we stop for a panoramic 180 degree view of the Sutlej valley far below. In a little over an hour we are at Rampur, visiting the wooden palace, ancestral home of Virbhadra Singh, Himachal’s current chief minister. Rampur wears a festive look with post Holi celebrations still going on.

Shongtong is another four-five hour drive from here so we’re driving at a relaxed pace. After Jeori we stop by a wayside dhaba for lunch. Drinking water comes from the gushing mountain stream passing by. The free-flowing water is also used to wash cars, sixty rupees apiece! After lunch we take to the road which is soon littered with loose stones falling off the hills. It’s a lonely road along the Sutlej between steep craggy mountains.

The roads wear a bombed out look with huge rocks and boulders beside the roads. Well, a lot of dynamite has been used to widen the road till Rekong Peo and beyond to Puh where military supplies have to be fed. By the time we reach Karcham dam, slowed because of the poor road condition, it’s nearly four. “It will take you just an hour to reach Shongtong!” my FGH host informs.

Half an hour later, in the fading twilight, we discover that the road ahead of us has vanished! There’s just a little red flag fluttering on the road to announce the danger. I get off the car and inspect. Nearly half a kilometer of the road has fallen off, maybe, because of a faulty dynamite-blast. It’s eerie. We turn back to discover a detour that nearly goes down to the level of the Sutlej and then rises again. The only prayer on my lips is, ‘God don’t send a car or truck from the opposite direction!’ We negotiate the stretch in silence.

Fear silences you. But up on the main too there is not much solace. Parts of the road are wet and slippery with the melting snow. Then we come across a stretch that is like a ditch with stones hitting my undercarriage. I wish my car had a four-wheel drive. It’s nearly dark when my car stops in the ditch. A prayer later it moves again, skidding, slipping. My little daughter begins to cry. Everyone is silent. But soon the worst is over. We see some lights. I spot a lone army man.

“How far is Shongtong forest guesthouse?” He points ahead, “You’re nearly there.” Our group of eight gives out a collective sigh of relief. The gate to the guest house is open but there’s not a soul in sight. After several honks the caretaker arrives. The guesthouse is spanking new but there’s no electricity.

“There was a problem yesterday,” the caretaker informs. But soon his wife brings hot cups of tea bringing some cheer to the cold evening. Besides the FGH and an adjoining army camp there’s nothing in Shongtong. The only shop that sells tea and stocks candles has already closed for the night. We go to his house and he re-opens his shop.

The children get engrossed in two blocks of snow outside the FGH that have not melted yet. The dinner by candle light is an experience I will cherish for long. Menu – egg curry, dal, rice and chapatis. As Nanku and his wife supply us hot chapatis our voices get drowned in a downpour, the pitter patter is accentuated by the tin roof of the guesthouse.

Hearing the rains after long!

Early next morning, bed tea in hand, from the guesthouse kitchen door Nanku shows us the white peaks of KinnarKailash. It’s white with fresh snow. The fir trees on the lower reaches look like they have been powdered with a coating of white. “When it rained here last night, it was snowing up there,” Nanku explains. The previous night I had heard one of our Kolkata guests whine, “Why have we come this far…what’s there in this place after all the risk.” That same lady was now saying, “Oh ma kishundor!”

A short morning walk to the bridge across the Sutlej and we see a handful of men and women waiting for the bus to Shimla. Apparently, for a long time no bus had arrived from Rekong Peo just 8 kms away. It means the road could be blocked by a fresh landslide. This was quiet common. But soon, to our relief, the bus from Peo arrives. “How’s the road uphill?” I ask. The driver grins, “Ekdum first-class!

Half an hour later, we set off for Peo. It takes us nearly an hour before Rokong-Peo, nestled at the foot of the KinnarKailash, comes into view. “O ma go…so beautiful!” our Kolkata friends can’t stop drooling. We stop again for pictures. Fifteen minutes later we are at Peo, now a much bigger town than the two-hotel town I had known ten years back.

Literally under the shadows of the white KinnerKailash mountains, Peo took our breath away. After thupka at a tiny wayside stall and window shopping at the crowded market, we set off for Kalpa that offers the best view of KinnarKailash. Driving uphill, through swathes of white snow amidst the Chilgonza trees we were at Kalpa in less than half an hour. The children began to throw snow balls at one another the moment they got out of the car. The view of KinnerKailash from here simply dazzles!

“Where is the Shiv-ling from which KinnarKailash gets its name?” I asked a local. He points to an invisible dot among the white peaks and saying, “There…you see that speck….it’s a different colour…it changes colour five times a day.”

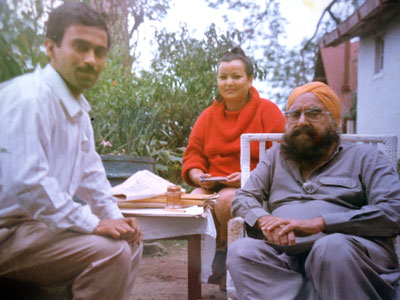

To be honest I couldn’t see the Shiv-ling. More attempts…and behold! I could spot a different color atop a small white peak. It was slightly orange. Later we met a young sardar from Mohali, a regular in Kalpa, who showed us the Shiv-ling through the tele-lens of his camera. It was clearly visible. “It’s a 70 feet tall rock,” he explained. And how come it changed color? “That’s got more to do with the angle of the light falling on the rock,” the strapping pony-tailed explained as we had lunch watching the glistening white mountains.

Legend has it that several hundred years ago Banasur, a local prince, meditated here and, pleased with his devotion, Shiva ‘expressed’ himself through the lingam. KinnarKailash is believed to be Lord Shiva’s winter-home. Every year locals do a ‘parikrama’ of KinnarKailash in the monsoon, a 40-km 4-day trek.

The best view of KinnarKailash is obtained in the morning when the sun’s rays tint the white peaks with pink and ochre. The scene, over the yellow dome of the Buddhist monastery straddling the scenic village, is ephemeral. Our own blinding view (because of the sunlight) from the mountain-facing balcony was not any less stunning. The Kolkata folks broke into poetry… “What our eyes have beheld today… the mind shall never forget…” Not surprisingly the only other tourist group we saw savoring the sights of Kalpa was another Bengali family.

Back at Rekong Peo we were disappointed to learn that our visit to Thangi, one of the most picturesque villages of Kinnaur, and Ribba, the home of the original ‘angoori’ made of grapes, had to be abandoned. “The road is blocked with snow,” we were told. Returning to Shongtong for the night, early next morning we returned to Karchham, from where we took the road branching off to Sangla. By noon we were at Sangla.

Our delight on seeing the snowcapped mountains around Sangla was short-lived. “The road to the forest guesthouse, on the other side of the Baspa is blocked with snow,” we were told. Fortunately the shopkeeper in Sangla who gave this information knew the FGH guard’s mobile number. The forest guard said, ‘Babuji wait for me, I’ll be there in half an hour.’ Half an hour later he was there. By then we had already taken up rooms in one of the few hotels that was open.

Since pipes were frozen most hotels had no water supply and not fully operational. The guard suggested that we trek down to “his” guest house to which we – barring three adults – agreed readily.

The excursion turned out to be a journey of discovery as we wound our way through the quaint village of Sangla. But, unlike a decade back, much of the old wooden houses with large-slate roofs had disappeared, giving way to ‘modern’ brick and cement structures. ‘The perils of development’, I sigh. Soon the river Baspa is visible and the guard points to a large cottage across the river on a mountain slope hidden by pines. It’s the guest house where we were supposed to stay.

Minutes later, running downhill, we are at the bridge across the Baspa. From here we get a panoramic view of Sangla village amidst white patches of snow. The road to the guest house is a slippery path because of the melting snow. Soon we are on the white snow-covered road in front of the guest house. Our feet go deep into the snow putting us off balance. Sangita, my wife actually falls flat. We guffaw.

Children start firing snow balls at one another. There’s so much fun and frolic, we forget about the hazards of just walking across to the wooden bungalow beyond the yard full of soft, white snow. The children keep falling off, but every fall elicits more laughter and fun. They are wet in their shoes but no one seems to bother. The guard brings a peeda, a flat stool, from his kitchen that the children use as a sleigh. Luckily, the guard has brought along a few packets of noodles that serves as our delicious lunch. From the Palava hut at the edge of the compound the scenic beauty of the river below and the village above, framed between snow clad peaks, is simply out of this world.

The trek back to Sangla market is arduous but the quaint sights and sounds keep us going. At the Hindu-Buddhist temple we take a break where locals give us a bag full of apples – offerings to the temple. The temple courtyard also serves as the community center where locals, mostly old men and women have their unending adda and steaming glasses of tea. These temples reflect a unique Kinnauri style of woodcraft architecture made by gifted local craftsmen.

By the time we reach the market it’s already dark. The family retires to the hotel. After my tipple I slink to tiny shop that is frying fish. It’s our last evening and I want to make the best of it. The night is cold despite the rum, quilts and Sangita. It is difficult to believe we’re into the first week of April.

Next morning, before returning, we drive down 14 kms to Raccham. This valley, with meadows turned snow-white, is easily the most beautiful place in Kinnaur. Luckily, it is still not colonized by the tourist promoters and retains some of its unique Kinnari charm. Chitkul, the last village some 10 kms further up is the last outpost of this tribal district.

e gave Chitkul a miss for want of time. “It’s the actual Switzerland,” a local entices us. ‘Switzerland does not have snow with such rustic charm,’ I wanted to tell him.

The author’s novel ‘The Sergeant’s Son’ was recently published by Rupa.

Ashim Choudhury

Print & Email

Print & Email